In Part 1, I considered student learning outcomes, the foundation of good course design, and how they relate to my learning goals in teaching Korean popular culture. In Part 2, I cover how I determine to how to evaluate what students know or can do by the end of the course (assessments) as well as the kind of activities that would help them develop the knowledge and skills they would need (assignments).

I cannot stress enough that if you are teaching your course online, in a hybrid scenario or face to face, you are still teaching in a pandemic. This means flexibility will be key to managing unforeseen circumstances can impact you and your student’s engagement in your course. Such circumstances can include your students being quarantined or getting sick, or someone they live with experiencing the same. We can design our courses to be rigorous and address such disruptions. I try to keep this in mind when thinking about assessment and assignments in my course. Don’t be so hard on yourself to design the perfect course either. Remember, we’re in a pandemic, y’all. Your class is going to be good because you have a wealth of information and your sparkling personality.

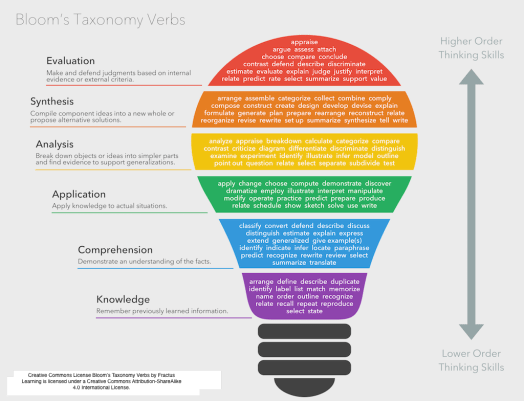

Let’s start with assessments. My highest-order thinking goal is for students to analyze Korean popular culture. I’m going to measure how well students can do this by having them write a long-form web article (1500-2000 words) where they use scholarly concepts to interpret multimedia sources. This is the major assessment of the course. The rubric (later post!) that I will develop will ascertain how well students do such things as articulate a thesis, use sources as evidence and create a well-supported argument.

But before students can do any of these, I’ll have to teach them and give them practice. This is where assignments come in. We also call them learning support tasks. They are basically anything that helps students acquire fundamental knowledge and skills necessary for later higher-order thinking. They are low-stakes assignments, worth a few points in a student’s overall grade, and cover a small portion of a larger assignment.

I start using these assignments in week 1. Students choose their own topics on the first day of class, so they will be motivated because they are able to focus on things that interest them. K-pop cover dance your jam? Have at it. Down with K-drama? Cool. Every other week they will post and talk about sources they find related to that topic so they are regularly engaged with their topic and sources.

In addition, students will write short-form articles (200-250 words) every other week. They are worth 2% each and are always on the student’s topic. The short-form articles are also cumulative. For example, for the first one, I students focus on just crafting a main, controlling idea. The next one, in addition to crafting a main, controlling idea, they also focus on using sources to support the argument. You get the idea. Because they are low-stakes, they give students the opportunity to develop knowledge and skills without worrying about mistakes costing them in terms of their grade. They are also motivated because they are following their interests. Not only are these low-stakes assignments connected to each other, they also form the foundation for the long-form web article. The long-form article represents an extension of the writing they do for the short-form assignments, so that towards the latter part of the class, they are largely focused on revision.

Normally, students would have probably 6 of these short form writing assignments. For this course, I reduced the number to 4 and focused each one on just the most important things I wanted students to be able to do. For example, normally I focus on having students do research with scholarly sources. However, this is not a research class, and I’m more interested in having students apply certain scholarly concepts to examples they encounter in Korean popular culture. So I spend more time making sure they can apply the concepts to music and music video, K-drama and film than finding scholarly sources. That type of scholarly research is not part of my student learning outcomes. Coco Chanel once said: “Before you leave the house, look in the mirror and take one thing off.” Similarly, I looked at my syllabus and ended up taking out several assignments. I realized that some assignments were redundant. I found I could combine others because they were doing similar work towards my student learning outcomes. Less is more. I feel my course still covers a good range of material and challenges students.

Finally, I considered how I can make this setup work in a pandemic. To anticipate disruptions in students’ lives, I will drop the lowest grade for short-form writing assignment. I will also provide copious opportunities for extra credit. This can ease students’ anxiety over getting sick or having to be out for at least two weeks. This way, students do not have to worry and can do their best when they can do their best. This may feel strange for some people because they have an idea in their heads about how their course should go. But when your course is well-aligned, it can reduce anxiety because everything is centered around what students will learn. At the same time, you can still have some spontaneity in your course. Discussions can be unpredictable. Student choices about topics will run the gamut. And if something isn’t working, feel free to change it on the fly.

Designing your course with assignment and assessments that are linked to your student learning outcomes and anticipating disruption will help you tremendously in the coming semester.

Teaching K-pop, Part 2: Assignments, Assessments (ew!) and Modalities by Crystal S. Anderson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.